Pacific Community Ventures is a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI), which means we invest dollars and people in underserved areas to create jobs and economic opportunity. Here in California it’s small businesses that are the jobs engine of the state. What isn’t so widely known is that the majority of California’s small businesses are started and run by people of color. Despite this fact, each year more than 50% of minority-owned businesses are denied access to the capital they need to grow and thrive. As a result, these entrepreneurs have to seek out alternative funding.

Tadu Ethiopian Kitchen is a popular and well-loved Ethiopian restaurant with two locations in San Francisco. Owners Nani Tsegaye and Elias Shawel opened their first location in the Tenderloin at the close of 2014. In the first three years, the couple worked tirelessly to build their revenues and grow their team. So, when the opportunity to open a new location near the Warriors Mission Bay Arena came up, they jumped on it. Their bank and other traditional lenders said “no,” and it was only through the luck of a search on NerdWallet that they found nonprofit lender, Pacific Community Ventures, who said “yes.” With a $125,000 loan from PCV, Tadu Ethiopian Kitchen was able to hire additional staff and finalize the build-out for their Mission Bay location.

Nani told us, “I’m a woman, a minority, an immigrant, and a mother. I am the people who work for me, and that means I can create better jobs because I am them. Investing in businesses owned by people of color will really pay off and create more and better jobs for people like me: people of color, immigrants, women, parents.”

Funding America’s Real Job Creators

Across America women of color start more businesses than anyone else, and businesses with fewer than 100 employees employ nearly half of all US workers – that’s 56.8 million of us. That means the entrepreneurs that PCV serves are vital sources of jobs in their communities. These are businesses and communities that aren’t benefiting from “startup culture” and the capital that drives it. Ivy League-educated and well-connected tech and biotech founders in The Bay Area (San Francisco and Silicon Valley) and the Acela Corridor (Boston, New York, and Washington D.C.) account for nearly all of the venture capital investment in the entire United States. Women and business owners of color are being left out, and cities typically have fewer small business financing options which can cause entrepreneurs to reply on predatory online lenders when they don’t qualify for traditional bank or SBA loans.

At Pacific Community Ventures, we know things can be different. We envision a world of thriving communities where everyone has a fair shake. Our mission is to invest in small businesses, create good jobs for working people, and make markets work for social good.

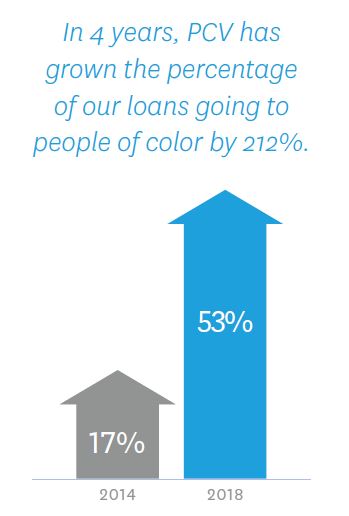

But what does that mean in practice? For 20 years, PCV has been at the forefront of investing in small businesses that create jobs — but that hasn’t always translated into funding businesses owned by people of color. That changed in 2014 when two factors converged that caused us to re-evaluate how we did business, and who we were serving: We started to see our lending program slow after 4 years of strong results; and we reevaluated our mission to focus not just on job creation, but on “quality” job creation.

What Changed, and What Does It Mean for CDFIs?

Pacific Community Ventures was founded in 1998 to provide venture capital, mentorship, and business networks to Main Street small businesses looking to grow and create jobs in underserved areas. The idea (which we call “impact investing” now) was an innovation at the time. We know our approach works, and that investing in small, local businesses fosters equitable growth and shared prosperity. During the height of the previous recession our companies had job growth levels at 12% while every state in America was reporting declines across the board. It was in the recovery from that recession when banks pulled back their lending, and small business owners told us they needed fair and affordable loans just as much as they needed our equity investments.

In 2012 we began to sunset our work as an equity investor and launched our small business lending program. Every day, 8,000 small business loan requests are declined by banks across America. PCV’s approach is different: As a CDFI our loan program provides affordable small business loans from $10k — $200k to bridge the “missing middle” between startup loans and financing from banks.

In the first years of our program we saw steady growth as most large businesses recovered from the recession, and banks started lending again, but that “missing middle” was still missing. In 2014, though, things changed. Every year, PCV does an annual social impact report. As we turned the corner into 2015, we looked back at the prior year and started to ask harder questions about our lending and why it was flatlining. Driven by a few staff members at all levels, we set out to find if it was a problem in marketing, a problem in underwriting, or some other market force.

This work took time. We tested several new marketing approaches throughout 2015 to reach small business owners. We started looking at where our small business loan applicants were falling out of the pipeline and why, and then tried out several ways of tweaking our underwriting criteria and processes to move more applicants through at a quicker rate. We had no idea how prescient that second part would end up being (more on that later!)

Throughout 2015 we also took up another major organizational change: discussing our mission, and if we were truly meeting it. In the past few years, the U.S. unemployment rate dropped below 4% for the first time in a generation and social impact investing finally entered the mainstream. Yet almost half of American workers were (and are) stuck in low-wage jobs with little opportunity for advancement, the number of small businesses is at an all-time low, and race and where you’re born remain some of the biggest factors influencing financial success in life.

We’d historically focused on supporting small businesses and investors to create jobs in underserved communities — but creating jobs alone was no longer enough to address rising inequality. As an impact investor, we realized we had to ensure our capital was first and foremost creating good jobs with living wages and benefits – so after a year of discussion in 2015, we began 2016 by making an organization-wide commitment to support the creation of quality jobs both in our own work with small businesses and with the broader social sector. Our vision is to create stronger communities from the bottom up through making quality job creation the new norm.

The Market Landscape and What It Meant

Getting back to how we diagnosed our own lending program: we spent two months reading Federal Reserve studies, SBA reports, and other sources of market intelligence to see if our lending program (the “missing middle” of $10k — $200k) was still needed. We found that small business lending started rebounding in 2014, and in 2018 experienced record highs amongst big banks and institutional lenders like community banks, credit unions, and SBA lenders. California small businesses saw an 80% jump in loan demand as the economy improved. But still not all small businesses are able to get funding from these traditional lenders. This has led to the growth of independent lenders (FinTech companies, some downright predatory) filling the gap with a record number of loans.

At the same time, the “missing middle” that PCV created its loan fund to fill during the last recession has become more muddled. Small business owners looking for capital between $10,000 – $200,000 still go to banks first. If they’re turned away, that range of capital is also covered in very general terms by SBA lenders, community banks, credit unions, FinTech, and other CDFIs (at least in the Bay Area market). SBA programs still need a 620 credit score in almost all cases. Fintech has created greater availability but with generally higher rates and shorter terms. Local CDFIs have a variety of programs for the missing middle but many of them are very specialized. That being said, all of these options mean a much more crowded marketplace than what existed 10 years ago.

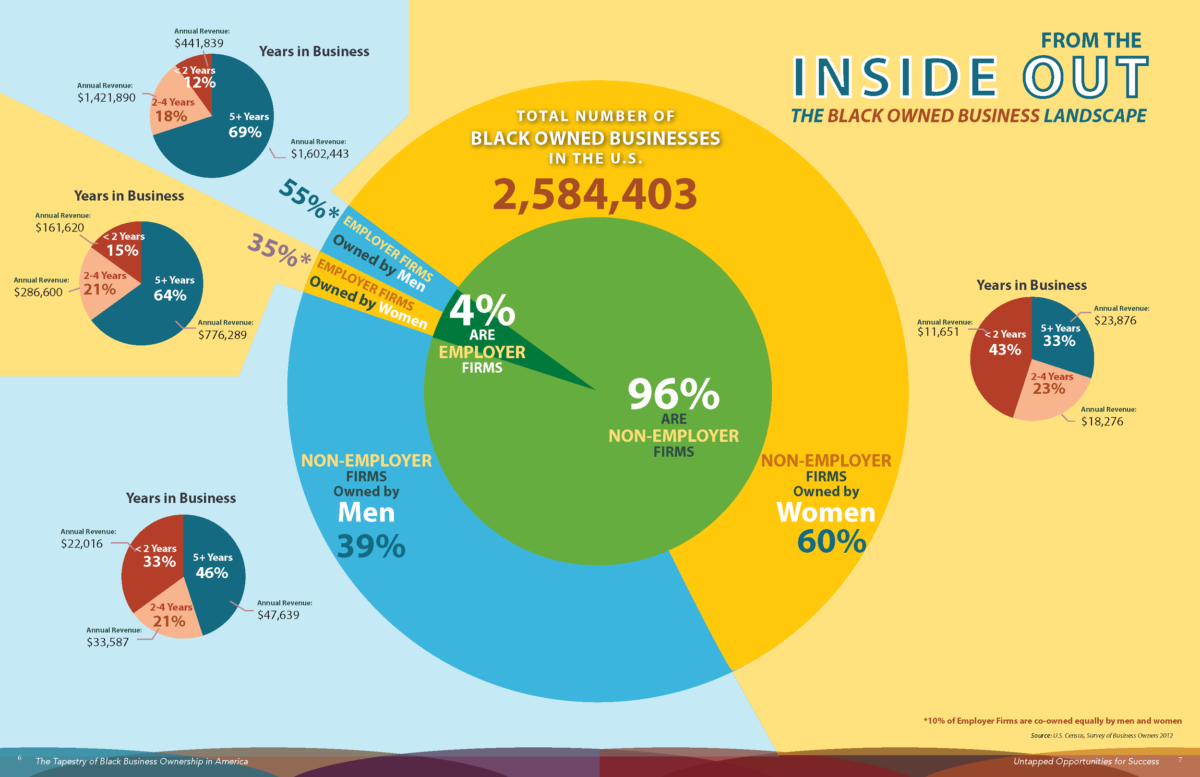

When we started our loan program, most small business owners in California who needed loans up to $200,000 were being declined across the board. After years of economic recovery, many business owners who needed that amount were now being funded. But, from both our research and Federal Reserve research, listening at community events, and by examining our application pipeline, we found that people of color and women were still being underserved.

According to Kauffman, one of the three reasons minority business owners underperform is lack of “sufficient financial capital to buffer losses, achieve efficient scale, and exploit business opportunities” Several studies point out that Black and Hispanic business owners are denied more often because they have less start-up capital (Fairlie and Robb 2008), less human capital (Lofstrom and Bates 2013), lower credit scores (Robb, Fairlie, and Robinson 2009), no or low collateral, etc. Black- and Hispanic-owned firms are denied more often, charged a higher interest rate and more discouraged to apply for a loan. Although some may argue that it is ‘rational’ for banks to deny riskier and less credit-worthy customers, the writers at Kauffman find overwhelming evidences of higher loan denial rates and higher interest rates charged for Black- and Hispanic-owned firms even after controlling observable and relevant variables. They suggest “the large gap be explained by racial discrimination.”

Women and minorities start more businesses than anyone else, and the businesses they start create jobs and opportunities in underinvested communities. Women- and minority-owned firms apply for the same types and amounts of small business loans as their white counterparts, but because of the circumstances just mentioned, they receive lower final loan amounts and higher interest rates.

The SBA guaranteed $5.1 billion in loans in California last year — most of it through large banks. Only about 2 percent of those borrowers were African Americans, a sharp drop from pre-recession levels. Latinos, who own more than 23 percent of businesses in the state, received just 13 percent of those loans. Minorities are less likely to apply for bank loans for fear of rejection, according to various studies. When they do apply, they get turned down more frequently than equally creditworthy white-owned firms.

The Decision: Serving The Underserved Means Driving Capital To Minority Business Owners

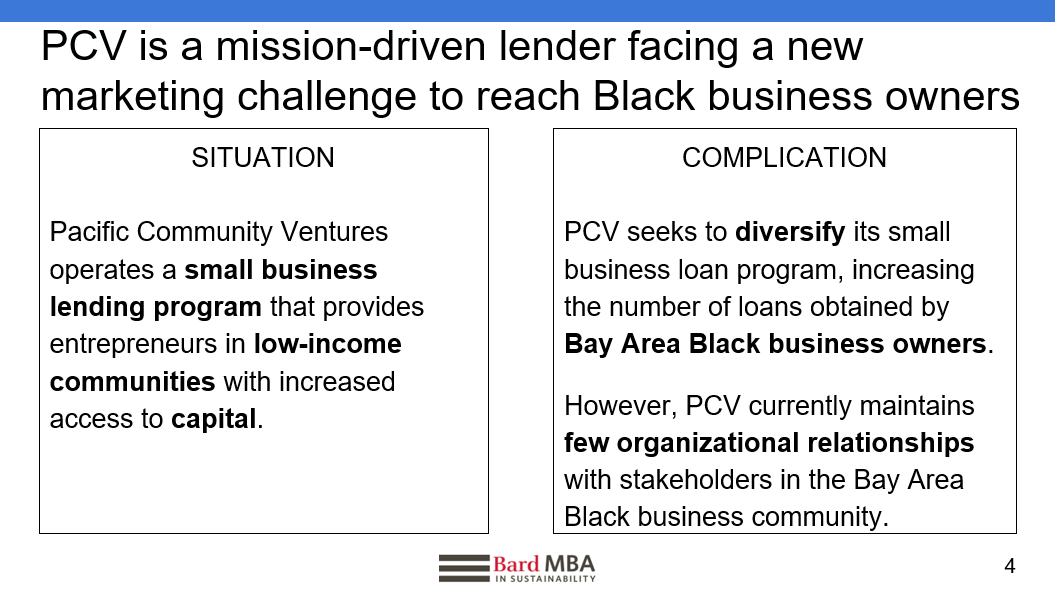

Once we made the decision to focus our loan program on the most underserved borrowers in Northern California – business owners of color – the next question we had to ask was: how?

PCV has been serving California for 20 years, and most of that time has been spent in and around San Francisco. As rising rents and gentrification pushed more and more people of color out of San Francisco and into the surrounding counties, we had to address our obvious weakness. How do we talk to communities and work within communities that we’re not from? We wanted to find ways to build trust and partnerships, and that had to start with authenticity. So we did two things: research and conversations.

We needed to learn more about the kinds of businesses that people of color were starting and running in the broader Bay Area, what those businesses needed to grow (and grow sustainably), and what grassroots organizations were already active in these communities. The reasons for asking these questions went much deeper than a marketing exercise – it went to the core of our programs. Even the most successfully-messaged product will fall flat if it doesn’t solve the challenges that people have or if the person delivering that message isn’t trusted or seen as authentic.

To start answering these questions, we knew we needed some outside help – someone who wasn’t as close to our program and our goals. One of our Board members teaches in the MBA program at Bard, and invited PCV to pitch our new loan program goals as a research project for his class. The class liked our pitch and took up our nonprofit alongside five others for the semester. In the ensuing months, PCV worked with a team of amazing MBA students from Bard who interviewed small business owners of color across the Bay Area, spoke with organizations already on the ground there, and researched the real addressable market (how many small businesses owned by people of color are there, how many need capital in a given year, what industries are they in, and what are their financial situations).

The students did great, thorough work, and presented us with results that really got us thinking. At the time, we thought PCV’s long-standing underwriting criteria was very flexible, but we found that we were approaching borrowers in a manner similar to banks, and that most small business owners of color didn’t meet our guidelines even though they were running great businesses. We also found that most business owners of color needed smaller loans than we realized, and they were running smaller businesses than we were used to funding.

The team also found that the key to our success would be building trust. Because we weren’t physically located in every community we wanted to work in, they suggested our best path wasn’t to market directly to small business owners, but to approach community organizations, local community banks, and other grassroots nonprofits and merchants groups with the value of our lending program. As the students said, “Partnering with local, mission-aligned organizations serving business owners of color and whose services PCV’s loan product and advising complements could facilitate trust and increase qualified leads.”

Changing The Way We Do Business

The research led us to reevaluate our criteria for loans, and how we evaluated whether or not a business was a good fit for our program. First, we created a proprietary underwriting matrix that that gives us flexibility in evaluating credit packages. We look at the “whole borrower”, so areas in which an applicant may be weaker would not automatically disqualify them, but rather could be offset by other areas where they were stronger. For example, strong business cash flow could overcome a very low credit score, enabling us to make a loan that others would decline. This is in contrast to underwriting approaches of organizations like the SBA, where one negative rating can disqualify the whole application.

Second, upon learning that Black-owned businesses tend to be smaller and often newer, we eliminated our minimum thresholds, which had been $200,000 in annual revenue and at least two years in business. We still rigorously review each application using our underwriting matrix, and we will not make loans to pre-revenue businesses, but we no longer automatically disqualify businesses based on revenue and time in business thresholds.

For example, Tammy Foxx, the owner of Bridal Fitness Coach in San Francisco, wanted to open her own studio rather than renting space in someone else’s, because she was losing clients due to scheduling challenges. While her 2018 revenue was only $75,000, she had a history of growing her business. Securing a commercial space in San Francisco would not only allow her to expand her own business but also give her the ability to rent space to other fitness coaches. PCV provided her with a $95,000 loan to secure the lease, purchase equipment and supplies, and increase marketing.

Third, in 2018 we again modified our underwriting process, this time to include Global Debt Service Coverage, which allows us to consider a borrower’s personal and business income in making lending decisions. This is especially important for entrepreneurs of color because while many have fundamentally good businesses, with a shorter time in business they often have not yet reached a debt-service coverage ratio strong enough to independently support the loan requested. For example, by using Global Debt Service Coverage — the ratio of operating income available to debt servicing for interest, principal and lease payments — we were able to make a $100,000 loan to Javier Sandes. Javier wanted to expand his Argentinian restaurant and catering business, Javi’s Parrilla, which is located in a low income neighborhood in Oakland. He’d been turned down by his bank, because his loan request was too small for them and his business too new. Had we only considered the more traditional ratios that banks tend to use, the loan may have been declined.

Finally, PCV doesn’t offer a “loan” product. We offer a “loan + advice” product, because we believe that for small business owners to succeed, they need capital paired with mentoring. Advising is provided through our national mentoring platform, BusinessAdvising.org. In 2018 we served 716 entrepreneurs, including all our borrowers. 74% of the entrepreneurs were diverse: 59% women, 50% people of color. Among entrepreneurs who identified as people of color, African Americans were the largest group, with 147 enrolled in our program, almost double 2017. While the businesses came from all 50 states, 55% (391) were in California, 30% (209) in San Francisco, Alameda, and Contra Costa counties.

Lesly Simmons is an example of the types of small business owners we serve. Leslie, the founder of Simmons Creative, a San Francisco-based conference production company, is currently taking advantage of her fourth mentorship engagement. This time her focus is on her company’s growth strategy. She has been paired with Oakland-based Uzo Ometu, who works as a Content Partnerships Manager at YouTube. They have been working together for several months, creating, prioritizing and executing a variety of growth tactics.

While we were making these big changes so that we could underwrite the whole borrower and ensure our loans were really in service of our mission, we had to get out in the community to start doing the ground work of building trust. We got the ball rolling by looking at some of the bigger cities in the counties we wanted to work in, and started Googling their merchants’ groups, nonprofits that worked with small business owners, and local community lenders. We put all of the groups on a list by city, and then we started making calls to get out and meet people, tell them about our program, and find out how we could complement the work they were doing on the ground.

The idea was simple: we may not have been a grassroots organization in, say, Richmond California, but we could find ways to offer ourselves as a value-added partner for those organizations. It took the better part of a year, but we started to make great connections, attend lots of local events, and began to make ties with local groups like Richmond Main Street, Richmond Chamber of Commerce, the Bay Area Association of Black Owned Businesses (BAOBAB), the African-American Chamber of Commerce, and on and on. We spoke at their events and found ways to adjust our program and our offers to their needs.

The Results

Our loan program was launched in San Francisco, and this continues to be an important market for us, representing 14% of total 2018 capital deployed. However, we’ve expanded our work to serve business owners of color in other counties like Alameda (57% of our lending) and last year Contra Costa (11% of our lending). We prioritized these counties because they’ve become increasingly diverse as gentrification, driven largely by the tech industry, has forced more people to move further east. For perspective, 44% of Alameda residents are Black, Latinx or Native American; 37% for Contra Costa county. Together these two counties have over 60,000 small businesses with employees, many owned by women and/or people of color who consistently face barriers when trying to access capital.

We’re proud that in four years our lending portfolio has gone from 17% people of color, to 53% people of color. And we’re not resting. Being a partner in the community means meeting the needs of the community for the long haul.

We’re once again examining our underwriting matrix and guidelines looking for ways to serve more borrowers. Our communities and the demographics within them continue to change and PCV wants to change to meet their needs.