Case Studies

The Michigan Good Food Fund

Using Impact Evaluation to Better Understand Community Impact

The Michigan Good Food Fund (MGFF), a $30 million public-private partnership loan fund that supports good food enterprises working to increase access to affordable, healthy food in low-income and underserved communities. This includes the range of businesses that grow, process, distribute, and sell healthy food that reaches those who need it most. Core partners include Capital Impact Partners, as well as Fair Food Network, Michigan State University Center for Regional Food Systems, and W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

The Michigan Good Food Fund (MGFF), a $30 million public-private partnership loan fund that supports good food enterprises working to increase access to affordable, healthy food in low-income and underserved communities. This includes the range of businesses that grow, process, distribute, and sell healthy food that reaches those who need it most. Core partners include Capital Impact Partners, as well as Fair Food Network, Michigan State University Center for Regional Food Systems, and W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

Diamond Place is a $42 million development project in Grand Rapids, Michigan that will bring together more than 115 units of affordable housing plus 22,000 square feet of retail space anchored by a community grocery store. Located in a USDA-designated food desert, this project will create an anchor of healthy food access for area residents, who also experience high poverty rates. In addition to the food and housing benefits, Diamond Place will create an estimated 200 construction jobs and 150 permanent jobs from the retail tenants.

“This type of development, mixed-use, mixed-income has been a model, but it hasn’t been done in Michigan at least on this scale too much yet,’’ noted the developers of the project. A mission-driven Community Development Financial Institution, Capital Impact provided a $3,645,600 loan to support the construction of Diamond Place. Part of the reason Diamond Place came in to being is because of a program administered by Capital Impact Partners called The Michigan Good Food Fund (MGFF).

Growing Michigan’s Food Future

To understand the importance of a project like Diamond Place, you have to understand that more than 1.7 million Michigan residents—including 338,000 children—live in communities with limited access to the nutritious fruits and vegetables they need to thrive. Children and families, often in lower-income rural and urban areas, often struggle with obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other diet-related challenges. Communities of color are disproportionately impacted. However, it goes beyond poor health outcomes. These same communities also often face high rates of unemployment and lack of economic opportunity, and children of color in Michigan are disproportionately poor. While Michigan is an agricultural powerhouse, the infrastructure that connects farmers to distributors and markets needs to be strengthened to meet the growing demand for healthy, locally grown food.

As a national organization working on a hyper-local level to address critical issues of social and economic justice – such as limited access to food or affordable housing – Capital Impact Partners established an office in Detroit to better focus on communities in the city and Michigan more broadly. That included establishing The Michigan Good Food Fund (MGFF), a $30 million public-private partnership loan fund that supports good food enterprises working to increase access to affordable, healthy food in low-income and underserved communities. This includes the range of businesses that grow, process, distribute, and sell healthy food that reaches those who need it most. Core partners include Capital Impact Partners, as well as Fair Food Network, Michigan State University Center for Regional Food Systems, and W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

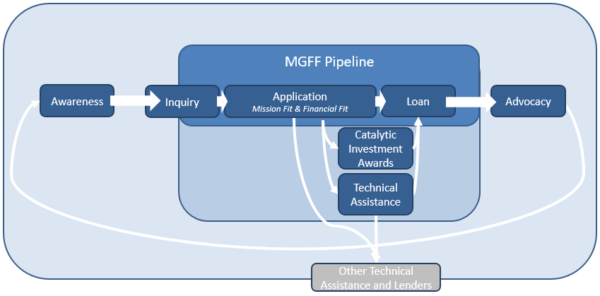

Through the MGFF, Capital Impact provides flexible, patient capital to good food enterprises often overlooked by traditional banks. That mission driven lending is bolstered by strategically-aligned business assistance and other forms of catalytic investment to help entrepreneurs grow their ventures and prepare for financing.

Through this multi-pronged effort, Capital Impact not only hopes to increase access to healthy food, but also improve the health of children and families, spark economic development and job creation, and create more inclusive food systems that provide key opportunities for communities of color who have traditionally been excluded from this sector.

Impact Evaluation Was A Key Founding Principle

Diamond Place is just one of the many examples of this initiative. Since its 2015 launch, the program has invested more than $13 million in good food enterprises, supporting 300 businesses with financing or business assistance and created or retained 600 jobs across the state food value chain. While impressive on the surface, the partners still had questions about the impact they were having.

When the MGFF partners launched the initiative, they were still learning more about the exercise and practice of impact evaluation. Building an impact evaluation process into the Fund was first inspired by a key funder, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, who gave them a specific budget for evaluation as part of an overall administrative grant. “Our funder embedded funding for evaluation into the scope of the work, which we may not have known to do at the onset. That insistence showed us the value that the impact measurement and evaluation discipline can bring,” said Olivia Rebanal, Director of Inclusive Food Systems at Capital Impact Partners.

This was also the first time that Capital Impact Partners, a 35-year-old national CDFI, managed a comprehensive impact evaluation plan conducted by an independent consultant. “All of this was new to us,” said Olivia. “We were really open to it. We’d seen the values, outcomes, and conclusions it could bring.” The Michigan Good Food Fund initiative and its evaluation has been an excellent way to learn about the rigor involved in impact measurement and management and all the value it brings.

PCV’s Work and the Value of Impact Measurement and Management

To determine and track progress towards these goals and to better understand the social, economic, and environmental impacts of the program’s activities, the Fund commissioned a developmental evaluation of the program’s outcomes in its first years of operation. As a developmental evaluation, the Michigan Good Food Fund’s partnership was intended to improve the initiative’s social and economic outcomes over time. Pacific Community Ventures was tasked with evaluation of the Fund’s social and economic outcomes.

Olivia said, “Prior to my arrival at Capital Impact Partners, we were involved in impact evaluations as a subject, so we were interviewed and evaluated, but we were not a full partner in the process. Now, we have a direct relationship with PCV as the evaluator firm for our initiative, so we are able to wholly participate in the design of the evaluation process and its products.” Learnings from this evaluation work is informing impact tracking and evaluation in other initiatives. “It’s really important in social impact measurement work to have an internal ally and advocate from the implementation and administration partner, to maximize its value within an organization. We’ve come a long way since then! The evaluation process is now fully collaborative from administration to evaluation.”

Learning Through Developmental Evaluation

Our early evaluation findings showed Capital Impact Partners that the development and implementation of the Fund was strong and effective, at the same time we found they weren’t doing the best job of being a strategic leader within the Michigan Good Food Fund, leaving other partners feeling unfulfilled.

“We wouldn’t have seen that ourselves,” said Olivia. “We could have just worked hard and felt that we were doing great – but it was informative to read it. It wasn’t easy, and it’s still not easy. It’s like an employee review, and you’re being told you’re doing this great, that great, but you fell short here. We really took that to heart. We improved in areas like providing more strategic direction and facilitating collaboration.”

“After the first year that Michigan Good Food Fund existed, the partners started to have more buy-in to the evaluation work, and it’s been easier each year,” said Olivia. Capital Impact Partners had always collected rigorous data for investor reporting on impact. While it was rigorous, Olivia and her team quickly realized that while their financial reporting was outstanding, their social and economic reporting didn’t yet have the same rigor as what PCV provided.

Using Evaluation to Better Understand Community Impact

“What do we do with an impact evaluation? We hear and listen,” said Olivia. “Evaluations can be hard for organizations that don’t want to hear criticism. It takes a willingness to accept there are opportunities to growth. You can say all day long that you’re hitting goals, but to have an external expert give you advice is special, and it takes a special organization to accept and acknowledge it. We’re using our impact evaluations to re-focus our work in communities if meeting our mission of bringing resources where it is needed most. We’re using it to improve our pipeline development and to mature our programming.”

The evaluation didn’t just highlight the programs’ many successes. It also found opportunities for the Fund and its partners to improve. One theme that emerged during stakeholder interviews was the perceived lack of variety in the types of food enterprises that were applying for financing. While grocery stores and food retailers were really prevalent in the pipeline, some of the Fund’s partners anticipated higher demand from food processors and aggregators. Pipeline analysis showed that while grocery and retail businesses accounted for the highest share of financing inquiries, processors were actually a close second. The impact evaluation demonstrated that the core challenge may not be soliciting the interest of processors and producers, but the greater barrier was in moving them through the pipeline.

Another area for improvement that the impact evaluation uncovered was in reaching underrepresented and minority enterprises. This was a founding principle and key priority for Fund’s partners, given their focus on promoting racial and social equity. Although PCV found the Fund was strong when it came to connecting with women entrepreneurs, it was important for the Fund to continue cultivating racial diversity. One core partner indicated that building authentic relationships is critical for reaching underrepresented entrepreneurs: “It’s about relationships and it takes time, it takesmonths and months or years of work.” With this trust and rapport, food entrepreneurs of color are in partnership with the Fund, working together to scale, grow, and improve.

Lessons For The Fund, Lessons For The Field

Of the businesses the Fund supported last year, 88% are located in economically distressed communities. Those businesses retained and created 533 permanent jobs. Construction and renovation activities among MGFF businesses supported another 80 jobs. The Fund has also grown their portfolio to meet their mission: 55% of all businesses receiving Fund support are owned by women, 52% of all businesses are owned by people of color, and 100% of loan recipients report implementing sustainable environmental practices. “I think we’re doing great,” said Olivia, “and we can base that statement on the data analysis that PCV provides. We collect data on race, ethnicity, income level of entrepreneurs, job quality, opportunities for workers in the communities we want to serve. Collecting and reporting that information and knowing how to disaggregate it is really important. PCV has helped us inform and shape our data tracking system, informed the metrics we collect, and helped define which are most important.”

Oliva also shared that the impact measurement and management approaches employed as part of the developmental evaluation are applicable across programs and initiatives. When she shares the evaluation with other initiative directors at Capital Impact Partners, they’re intrigued and embed it into other initiatives. As for the Michigan Good Food Fund, Oliva says “I’d like to see us be even more explicit about our objectives. As we collect data, we need to set new benchmarks each year. I’d also like to have the social impact work we’re doing become more ‘socialized’ across the CDFI space, and across food system funders. We do a great job of doing financial reporting as an industry, and we have an opportunity to lead and educate our funders and investors on the social impact data we should be collecting.”